Paul Bouvot is the man whose design proposal for one of the most famous cars of all time was rejected. The Peugeot 504 was created in an internecinal tug-of-war between Peugeot’s own studio and Pininfarina. Pininfarina’s won.

Monsieur Bouvot shouldn’t have felt dejected altogether. After all, his design for the front of the 504 was accepted over Pininfarina’s. The 504’s trapezoidal light signature and slatted grille made it one of the most recognisable car shapes in the world. The customers didn’t know about the graft. They just liked the car. And it was the customers who made it classic.

As Peugeot’s design director throughout the 1960s and 1970s, it is his name behind their most ambitious single project of that period – the 204. The 204 was a light family car with advanced front wheel drive engineering new to Peugeot. The transverse engine layout afforded it brilliant space packaging, if not subsequent repairability. Sedan, wagon, van, coupe and convertible body styles were all on the drawing boards at once.

That car was a true collaborative effort with Pininfarina. Bouvot provided the basic shapes and volumes, and Pininfarina finessed the details. Despite the collaboration, it was Bouvot’s long-term desire to build a confidence and self-reliance on design at Peugeot, and he would cheekily park his Bertone-designed Lamborghini Miura right at the main gates of Pininfarina to subtly get the point across. It took some years for Peugeot to wean themselves off Pininfarina, but Bouvot eventually achieved his aim, posthumously.

How incredible it must have been to have lived in a time and place where, almost by accident, you could rub shoulders with Bugatti’s and Ferrari’s engineering and design teams. This is exactly what Bouvot was able to do from a young age. He was not from a monied family – the Miura had more to do with the Peugeot pay packet. It was more about growing up in a particular place in a particular time, and being shaped by the surrounding influences.

The flipside to this, sadly, is that it was also a dangerous time to be alive. In July 1944, aged 22, Paul Bouvot and his close friend Gilbert Cuinet were ambushed by a German patrol unit in Mouchard, France. Both young men were members of the French Resistance. The patrol unit made an example of Cuinet on the spot, and he was shot before Bouvot’s eyes. Bouvot himself was spared, arrested, sent to the Dachau concentration camp, and tattooed. The Russians liberated Dachau in 1945.

After WWII, Bouvot returned to a life of drawing, painting, and hanging around guys who owned Bugattis and Ferraris and raced motorbikes. He resumed working for Labourier, a tractor manufacturer. He started to build and race his own bikes. He bought cars, just one at at time. He would cut them up, and put them back together again, but shorter, faster and lighter. It wouldn’t matter if it was a Ferrari. At least one was! He even got around town at one point in nothing but his clothes and a tube chassis with an engine and headlights.

His confidence and skills were on the rise. Not just on the rise, either. He was better than others. Word was getting around about this artisan who was building his own barchetta sports car with a Simca engine. Its panels were beaten by hand. Peugeot’s boss demanded to see it and demanded to meet its creator.

From that meeting, in short order, Bouvot became the boss of Peugeot design. The work confounded and stifled him at times. The 504 experience was probably a case in point, although such a disappointment is not on the record. His more beautiful and audacious work was not given air time. Peugeot was a conservative company.

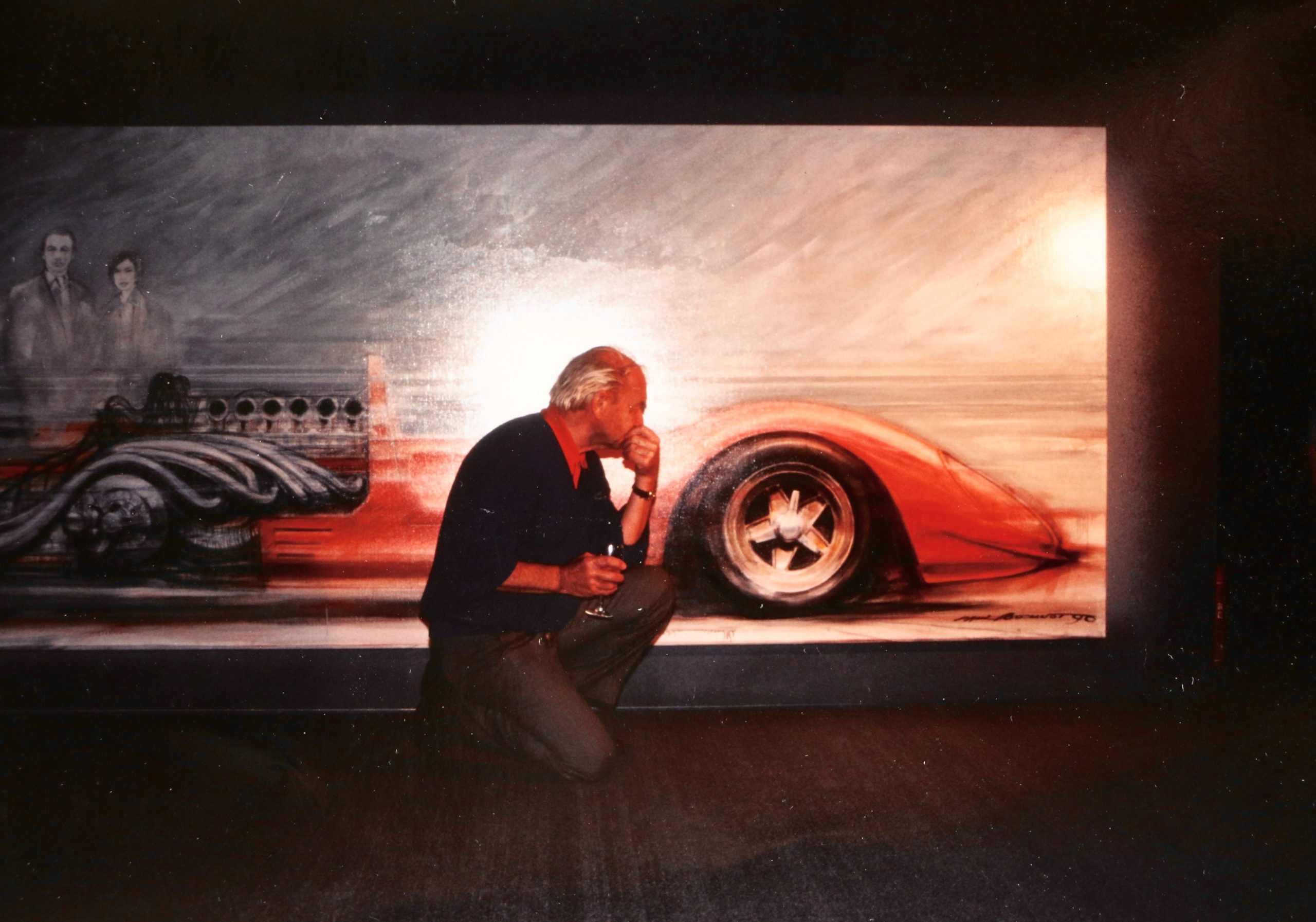

After retiring in 1980, Bouvot painted full time, day and night. His preferred themes were cars, engines, ladies and trains. He created 150 masterpieces, including the one where he appears to be posing by his own painting. A number were unfinished. It wouldn’t stop them being auctioned by famous art houses such as Pullman Galleries. One collector built a gallery onto his home that housed only Bouvot’s work.

His son Marc called him Paul Bouvot, or just Paul. He never thought of him as a father, because he was such a great presence and a great friend.

Like all of Peugeot’s post-war designers, he was an artist first and foremost.

Paul Bouvot died in 2000. You could spend all afternoon reading about him. Start by reading what his son Marc has to say about him in this piece by Classic Driver. Caradisiac hosts a translated piece on Bouvot which still reads poetically. Driven To Write has an engaging history on Bouvot and the 204, with plenty of readers adding commentary and insight.